Kayaking the icy waters

Alaska's world champion paddler crossed Bering Sea and Northwest Passage

By George Bryson / Anchorage Daily News

Suppose they came by sea.

Instead of walking across the Bering Strait land bridge during the last ice age, as had long been assumed, perhaps the first people to reach the Americas arrived here by boat -- as an increasing number of archaeologists and anthropologists now believe. If so, migration theorists curious about the journey might profit by talking to Martin Leonard III, an educator, surfer and adventurer who lives near Bethel, a city in southwestern Alaska.

Leonard, 45, is probably the only man alive to have kayaked the Bering Strait and then continued in a series of other trips over the top of the North American continent -- through the perilously icy Northwest Passage -- as far as the Atlantic Ocean. Along the way he formed opinions about such journeys.

One: Don't travel from east to west -- against the wind -- as a couple of Canadian kayakers did on their own Northwest Passage expedition about a decade ago. One of them lost all his fingers to frostbite.

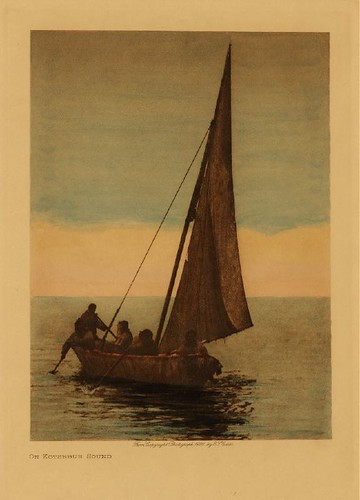

Two: Travel fast and light -- since the ice-free days of summer in the central Arctic are so fleeting -- and ride the surf whenever you can. That's how earlier Eskimo kayakers probably voyaged, Leonard says."There's documented Russian accounts that depict these kayakers going at superhuman speeds, beating sailing ships that are traveling 7 or 8 knots," he says. "And my thesis is: The way they did that and the way you win at Molokai and the way you paddle a kayak fast is to be a good surfer (riding ocean swells)."

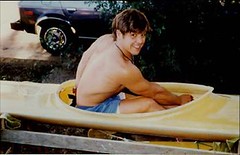

Wanting to put his theory to the test, about 10 years ago Leonard asked Hawaiian boat designer Hunt Johnsen to modify one of his prototype racing kayaks into the Arctic Cheetah. Which Johnsen did, crafting a sleek, 20-foot-long wisp of a boat that's exceedingly fast -- as long as you keep it upright.

With a rounded, highly efficient hull that's a mere 14.5 inches wide at the waterline beam, the Cheetah is tippy as a tightrope. Just listen to Johnsen's daughter, accomplished kayaker Spinnaker Wyss-Johnsen, describe her own experience when she first placed a prototype of Leonard's craft in the water outside her dad's boatyard in Hawaii.

"I spent the first day with my legs hanging over the side like training wheels," Wyss-Johnsen wrote in an article for Sea Kayaker magazine. "Once I got a bit of speed, the boat became slightly more stable. But just when I thought I'd gotten the hang of it, I'd find myself upside down again. ... To say that the Cheetah teaches you good bracing skills in a hurry is an understatement."

Yet it is extremely light, with a thinly glassed Kevlar hull that weighs about 35 pounds. When the wind's blowing hard and Leonard beaches the boat, sometimes he has to place a large boulder in the cockpit to keep it from blowing away. Just as he did in the Northwest Passage, fighting the frequent windstorms that battered the first leg of his two-year (1995-96) journey.

Which is just about the last time we heard about Leonard.

Unassuming and apparently indifferent to publicity, the Alaska geologist-turned-educator didn't bother to contact the media when he began his one-man Arctic journey, departing from the mouth of the Mackenzie River

(about 250 miles east of the Alaska-Canada border) on a coastal route heading east. Consequently, he didn't feel obligated to contact the press when he concluded the first leg, stopping in mid-August as an early winter settled on the central Arctic village of Umingmaktok, Nunavut.

Earlier, however, villagers in Tuktoyaktuk near the Mackenzie delta had grown concerned about Leonard paddling unseen through some of the wildest summer weather in a decade. Learning that he hadn't reached the next village on schedule, they called out a search party. Soon a Canadian Coast Guard helicopter was dispatched, and a brief story about the search ran on a Canadian wire service. The story was picked up by the Anchorage Daily News, which ran it as a small digest item. No subsequent story about Leonard's progress ever appeared. Consequently, when he returned to Anchorage that fall, a few friends were surprised to see him.

"Everybody thought I was dead," Leonard says.

They were wrong. Leonard was so alive that later that fall, he managed to win first place in the World Surf Kayak ing Championships in Costa Rica. He returned to the Canadian Arctic the next winter and completed his "Inuit Passage." A couple of years later he married Lucilla Alexie of Bethel, started a family and taught telecommunica tions at the Kuskokwim campus of the University of Alaska while doing his best to promote a kayak renaissance among hundreds of mostly Native students in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta.

At the same time, Leonard has remained active in the growing sport of surf kayaking, drawing a certain degree of worldwide attention whenever his feats are noted in magazines and Internet journals (most recently in the Web log of a traveling surfer who caught up with Leonard in Turnagain Arm, where the two kayak-surfed the local bore tide -- an account full of praise and wonder that ultimately dubbed Leonard "Mister Mysterioso").

So just who is Martin Leonard III? And how did he become Alaska's most unrecognized world champion?

Maybe by developing a few unconventional interests while growing up alongside the Delaware River in Trenton, N.J. It was there, he says, that he first got interested in kayaking.

"I lived in ethnic neighborhoods, so I was exposed to a lot of different cultures," he explained during a telephone interview from Bethel.

His father was Lithuanian; his mother was Italian. Some of his neighbors were immigrants from Slavic and Baltic countries that had long dominated Olympic events in canoeing and kayaking. As a kid, he belonged to one of the oldest German sport clubs in the nation and later traveled to Europe, competing in club soccer.

His interest in outdoor sports continued when he began attending a small college in western Pennsylvania with a nationally competitive soccer team, premier white-water kayaking in the nearby Appalachians and a strong program in sedimentary geology. Pursuing field work in geology ultimately led Leonard to Alaska, where he moved for good in the early 1980s.

Attending the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Leonard added an education degree to his bachelor's in geology, a combination that allowed him to work in the field for mineral companies and teach in rural schools all over Alaska.

He also met Arlene Williford, a fellow educator who shared his desire to kayak the entire coast of Alaska. The two were well on their way to doing just that in 1989 -- the year they were married -- when they decided instead to turn west and kayak to Siberia.

The expedition by about a dozen kayakers from the United States and England was part of a larger goodwill exchange celebrating the improved relations between the Soviet Union and its "divided twin" -- Alaska -- while also reuniting Siberian Yupiks whose families had been torn apart by political boundaries.

They would kayak from Nome to Wales, at the western tip of mainland Alaska, then cross the Bering Strait -- a distance of about 55 miles -- to the Chukotkan village of Uelen. Once on Soviet soil, they would continue southwest along the Siberian coastline to the town of Provideniya, where everyone would fly back home.

But that plan began to fall apart about halfway across the Bering Sea when a strong storm stalled the caravan a few miles short of the Diomede Islands.

Exhausted after paddling for 14 hours, some of the kayakers needed to be rescued. In a show of unity, the group decided to stay together. They were all rescued. Then when a motorized umiak began towing their empty boats to the islands, some of the kayaks sank (including a $5,000 bai darka -- a replica of the ancient kayaks of the Aleutians -- that had been donated to the expedition by kayak craftsman George Dyson).

The weather had been miserable for weeks. About half of the participants decided to call it quits, having at least reached the Russian possession of Big Diomede. Williford and Leonard decided to continue. They'd lost their visas when one of the towed boats capsized, but they ordered copies and waited for their documentation to arrive. About three weeks later, they completed the crossing to mainland Russia on calm, blue seas.

The nicest part was yet to come, Leonard says. For some reason, the Soviet authorities had forgotten about them, so they were able to explore the Russian coastline from Uelen to Provdeniya without the red tape.

"We arrived pretty much unattended and unescorted," Leonard says, "and so we saw some things probably other folks wouldn't have if they were on an organized trip."

One unexpected attraction was crossing paths with David Lewis -- the physician, author and world-famous mariner -- along with his anthropologist wife, Mimi George. After living in Western Alaska for several months, the couple had traveled across the Bering Strait to study the subsistence lifestyle of Native reindeer herders.

Then in his 70s, Lewis was mostly known for his navigational accomplishments, having completed the first solo voyage to Antarctica and the first circumnavigation of the globe in a catamaran while studying ancient forms of navigation.

"David is well-known for his maritime feats, but I became interested in his work as an ethnographer," Leonard says. "He was one of the first people to document traditional ways of knowing, as he did with the Polynesian mariners."

Unlike his counterpart Thor Heyerdahl, who asserted that the early people of the South Pacific were capable of traveling great distances but reached their destinations more or less by dumb luck, Lewis believed that the same people used pre-European strategies of navigation -- and he put his own life on the line on several long-distance sailing expeditions to prove so.

A few years later, in 1992, Lewis was planning another trip to the South Seas when he invited Leonard to join him as a crew member aboard a 30-foot gaff-rigged cutter, sailing out of Port Townsend, Wash. Leonard jumped at the chance. But once again, a twist of fate intervened around the halfway mark.

While anchored in Kauai, their boat was damaged by the passing whim of hurricane Iniki, by far the most destructive storm to strike Hawaii in recorded history.

"We had a couple of boats wash over, or fly over," Leonard said.

While waiting for repairs, he got to visit the boatbuilder Hunt Johnsen. He couldn't help but notice the striking similarity between a modified 20-foot sea-racing kayak in Johnsen's boatyard and the sketch of an old Native Russian kayak in the book Leonard held in his hand.

"So I covered the captions and any notations on the page, and I showed it to Hunt," Leonard says. "And I looked at him, and I said, 'What boat is that, Hunt?' And he said, 'Well, that's the Cheetah.' Then I uncovered the captions and notes, and it said it was a pre-contact Aleut design -- and it was exactly like the Cheetah."

A few years later, while living in Valdez, Leonard took delivery of that same boat's single offspring -- the Arctic Cheetah. The modified version included a cockpit -- as opposed to the "sit-on-top" style of the original -- with a sea skirt designed for northern conditions. He planned to take it as far north as he could, exploring the Northwest Passage.

This time, however, Leonard would be traveling alone -- his marriage with Williford had broken up a year earlier. Still, he was confident the Cheetah was up to the challenge.

"It's extremely fast," he noted later. "That's it, really. It can get you from point A to point B like no other boat can. But there's challenges to that, like keeping it upright or keeping it straight, and that comes with the territory."

After the Cheetah arrived in Valdez, the middle-school students in the local boatbuilding class helped Leonard get it ready. Together they spent a week trimming it out with paint. All that was left to do was attach the thigh straps that help the paddler brace the boat.

"I was chomping at the bit," Leonard recalls. "It was painted and looking pretty and ... gosh ... I realized I hadn't even floated the thing yet. So I took it down to the harbor to float it. And people were saying, 'Yeah, get in! Get in!' And so I got in. And as soon as I got in, a little bit of wake or a little bit of wind came up and I went to brace ... and had nothing to grab onto -- and out I went.

"So it was a pretty fitting christening. I could already see the boat had a character."

(Anchorage Daily News reporter George Bryson can be reached at gbryson@adn.com.)