SeaKayaker Magazine

August 2005

Martin Leonard—A Passion for High-Performance Touring

An expert in ultra-fast cruising finds his inspiration in the kayaking traditions of the Arctic.

Text by Peter Bronski

Photos by Martin Leonard III

In the world of performance kayaking, there are paddlers whose accomplishments are so renowned that they become household names: paddlers like Paul Caffyn and Ed Gillet, Oscar Chalupsky and Greg Barton. Then there are those who remain resolutely out of the limelight, like Martin Leonard III. Leonard made a splash in the kayak community during the early and mid-1990s when he crossed the Bering Strait from Alaska to Russia, then paddled the fabled Inuit (Northwest) Passage from Alaska to eastern Canada.

Since then, he’s slipped back under the radar, all the while quietly pioneering a new brand of performance kayaking that blends innovative boat design with specialized skills and a unique philosophical approach to expedition touring and surfing. That philosophy is unfailingly holistic—from his knowledge of ocean conditions to the food he eats and the sunglasses he wears. “You don’t need a $4,000 boat and a carbon-fiber paddle to be a performance paddler,” explains Leonard. “It comes down to the entire system.”

In the early ’80s, the New Jersey native moved to Alaska as a telecommunications specialist for the University of Alaska at Bethel. The move landed Leonard squarely in the heart of Yup’ik territory, where he became immersed in a Native American culture rich in kayaking heritage. From his home along the Kuskokwim River on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in the remote southwestern part of the state, Leonard began plying the waters of the far north: the Gulf of Alaska, the Bering and Beaufort Seas, the Arctic Ocean. This is performance at the extremes, in an unforgiving environment on the edge of the Earth.

“If you look on the map, I’m definitely on the edge logistically, up here on the fringe,” says the 47-year-old. “I’ve been in Alaska long enough to know I’m somewhat out of touch, but I pride myself on doing my own thing.”

In many ways, Leonard is like a high-altitude mountaineer or a fighter pilot. His pursuit demands refined technique, specialized equipment and protocol, and a style all its own—one that’s unequivocally utilitarian. “For me it comes down to application. I need a work boat,” he says. “We’re talking about boats and a system that you take on the ocean and trust your life with. The objective dangers [are high]. Everything we do here is an expedition. It’s wilderness as much as most people are ever going to -experience.”

Still, Leonard insists that the principle of what he’s doing can be applied to performance kayakers in any ocean around the world (in fact, much of his earlier training and development took place on the North Shore of Oahu in Hawaii, rather than in the Arctic).

Over the last decade, he’s regularly logged 1,000- and, just as often, 2,000-mile seasons; no small feat when the ocean is locked up in sea ice and pack ice for much of the year. And during this time, he’s developed what he calls “a total paddling system: equipment, skill level and worst-case-scenario safety backup systems, which enable the paddler to best address the conditions and situations presented on the water.”

For Leonard, that “total paddling system” (TPS) comes down to developing an effective synergy among four critical components: boat construction (hull design and amenities), wing paddle technique, an alpine-style approach to touring and surfing. When such harmony is achieved, the result is speed. In the Arctic, speed is access, and the formula is simple: The faster you go, the greater distance you can cover in less time with less fatigue—a crucial advantage for maximizing the short northern summers.

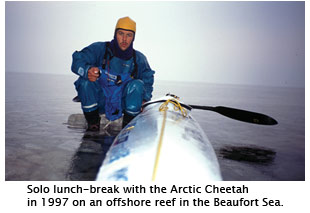

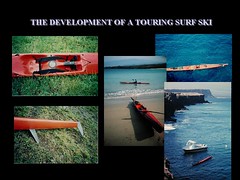

What does Leonard’s TPS look like in practice? The importance of the boat itself can’t be overstated. “Building boats for this environment is an art,” says Leonard. Like the system as a whole, the hull needs to be fast, which means long and narrow. The Arctic Cheetah, a one-time prototype out of Hunt Johnson’s Hawaii shop designed for Leonard’s Inuit Passage, was a major step in that direction—20 feet long, with a narrow, 14.5-inch beam.

The hull, too, needs to handle displacement out to its endpoints, taking into account the distribution of stowed expedition gear. Unlike performance-racing boats, for example, which are designed to carry their load within a narrow window focused around the boat’s center of gravity, performance-touring hulls need to function well when their full length is loaded with weight. “If you get in a touring boat at a demo day, don’t just paddle it,” Leonard says. “What happens when you put 100 pounds of gear in it? Know these answers before you invest—it may not be the boat you think it is. Spend time to test your boat…know how it performs in different conditions and at its limits.”

Just as important as hull design are details—hatches that don’t leak, bomb-proof deck fittings and a simple, fail-safe rudder system. It all speaks to the high demands of an extreme ocean environment that would challenge most boat designs, and where performance failure could cost you your life.

The design of the kayak is closely tied to the technique used to paddle it. Its extraordinary length and narrow beam are appropriate only for a paddler with the strength and balance to take advantage of its potential. The same is true for the wing paddles Leonard uses—they require a skilled and powerful paddler.

Wing paddles, according to Leonard, are the not-so-obvious but highly preferable choice. “I was told there was no application for wing paddles in touring. You couldn’t brace or roll with them,” says Leonard, who found that, contrary to popular opinion, wing paddles did have an important place in performance touring. That’s not to say wing paddles are right for all paddlers. “There’s no point in using wing paddles to improve your paddling efficiency seven to 10 percent on a boat that only does 3.5 miles per hour,” Leonard notes. But with the right boat, wing paddles give Leonard more of what he’s after: speed.

And in his pursuit of going ever faster, Leonard has adopted the mantra of the outdoor backpacking industry: Go light, go fast. “I take an alpine-style approach to kayaking,” says Leonard, borrowing a term from mountaineers. “You can’t move 30 pounds of gear as quickly as you can move 10 pounds of gear.” It’s a philosophy that marries well to performance touring—trimming weight from all parts of the system in the name of improving efficiency.

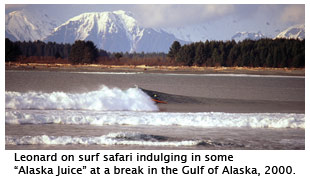

The final, and perhaps most dynamic, component of Leonard’s TPS is the refined skill of surfing. “I’m not talking cutbacks and roundhouses, negotiating the surf zone,” he emphasizes. “I’m talking about ocean swell surfing—open ocean running on a big wave train.” When it comes to achieving speeds in excess of 15 mph on the water, surfing is the key. It’s how you take a fast kayak, and make it go really fast. “It’s how traditional paddlers go fast; how people that win the Moloka’i Challenge go fast; that’s how I went fast across the Arctic Ocean averaging 50 miles per day, and upwards of 70 to 80 miles per day in the right conditions,” says Leonard. “We’re surfers first, paddlers second.”

Being a surfer first means becoming intimately attuned to Mother Nature, understanding the ocean environment you expect to paddle and, according to Leonard, borrowing the requisite skills and techniques from sea kayaking’s whitewater cousin. “They shouldn’t sell a sea kayak without a whitewater or a river boat attached,” he says. “The skills that you learn in a whitewater boat—ferrying, using currents, eddies—those microskills from the river translate directly to the macro ocean environment.”

Leonard points out that even huge islands, such as the Hawaiian island chain, create effects like eddies in the ocean. Not understanding those factors and conditions—tides, swell direction, wind direction, eddies, currents, wave height, steepness of the wave face, ocean depth (and hence, wave energy)—can hurt as much as help a paddler.

He uses the example of kayakers looking to cross a channel and make it to the beach to illustrate his point. “A lot of people are going to say, I don’t want to be in the tidal rip. They’re going to wait for slack water and mosey across,” Leonard explains. “If you’re a competent surfer, you’re not going to be afraid of the tidal rip in the middle of a channel. I’m looking for peak tides when I’ve got the biggest waves and the fastest water to get me where I need to go. And well, I’m going to beat those other people to the beach by a long shot.”

In simpler terms, it comes down to working hand in hand with Mother Nature, rather than against her. And that’s precisely how Leonard blazed across the Inuit Passage in record time—he wanted “the ice gone and big winds.” Knowing that Arctic winds prevail out of the northwest, he traveled east. With the wind on his shoulder, he made incredible time, “and those were happy times,” he says. “A little bit of planning and research can really go a long way. You’re not going to beat Mother Nature, and there are plenty of people, especially here in the Arctic, who didn’t live to tell their story because of that.”

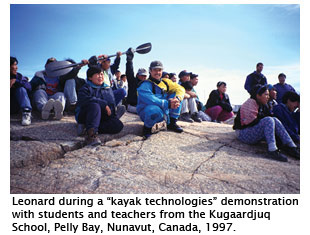

All in all, such synergy with Mother Nature and the techniques as a whole, are skills that Leonard, a kass’aq, or “white man” in Yup’ik, borrows from the early Alaskan cultures, and appropriately underscore the immense contributions of native paddlers to present-day kayaking.

![ct20015r[1]](http://static.flickr.com/4/5198507_9322f064fa_m.jpg)

![ct20014r[1]](http://static.flickr.com/3/5198502_ce292dbb9b_m.jpg)

As performance kayaking ushers in the future of the sport with cutting-edge designs and techniques, ironically, it moves closer and closer to kayaking’s heritage.

From Leonard’s perspective, today’s paddlers are “still playing catch-up” with the sport’s native forefathers. “Traditional paddlers lived on the ocean in their kayaks,” he notes. “There’s no way to equate their experience to that of paddlers today. From that standpoint, we’re all recreational boaters.”

That’s not to diminish the skill and drive of today’s performance kayakers. Leonard, for his part, has his sights set on a host of notable projects for the coming years. The consummate multitasker (he maintains a dizzying array of Internet blogs on all things kayaking-related) is intent on perfecting a performance-expedition touring ski.

He tries to spend as much time as possible on what he calls “Alaskan expedition surf surfaris”—paddling hybrid sit-on-tops, many of which are the creation of Hawaiian kayak designer Hunt Johnson, to remote breaks along Alaska’s 35,000 miles of coastline and surfing like a bandit.

He spends much time, too, giving back to the native communities of the Y-K Delta through the beloved sport they taught him: kayaking; something he wishes the greater kayak community would do as a whole.

In all, it’s an ambitious ticket, but one that Leonard, among all people, just might be capable of pulling off. “If you’re not unsuccessful—if you’re not failing—you’re not really trying to do anything,” he concludes. “I’m just trying to stay on the water. There are 10 mountains on my list, and if I climb half of them, I’m doing pretty well.”

Adventure writer Peter Bronski (www.peterbronski.com) profiled New York City’s Eric Stiller for Sea Kayaker’s February 2005 issue.

related LINKS:

Slide show of kayak surfing in Alaska

http://www.flickr.com/photos/martinleonard/sets/18315/show/

Slide show of Martin in Inuit Passage w/ Cheetah

http://www.flickr.com/photos/martinleonard/sets/24677/show/

Photo set Cheetah Expedition SOT Prototype

http://www.flickr.com/photos/martinleonard/sets/131300/

Dedicted to Vickie...We Miss You

______________________